For years, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, in Cleveland, devoted an entire wall in a gallery near the peak of its pyramid-shaped building to lauding Rolling Stone, the magazine founded by one of the halls biggest champions, Jann Wenner. Rolling Stone has always incited its writers to take risks, an exhibit placard read, but that was debatable, especially if the latest issue for sale in the gift shop happened to feature Jenny McCarthy or James Corden on the cover. The other music publications in the hall, confined to a small display in the basement, included Crawdaddy!, which preceded Rolling Stone by more than a year; Fusion, which was distinguished by its mix of grad-school intellectualism and high-level satire; and, most unjustly, Creem, whose masthead boasted that it was Americas only rock n roll magazine.

Creems staff members knew that the magazine was never the only one covering rock and rollthey meant that it was the only one that mattered. Many readers agreed, and efforts have long been under way to elevate the magazines place in historyfrom two short-lived attempts to revive Creem to a glossy coffee-table book, published in 2007, and the new documentary Creem: Americas Only Rock n Roll Magazine.

Creem was the brainchild of an Englishman named Tony Reay, who worked at a combined head shop and record store owned by the combative entrepreneur Barry Kramer. The first issue was published from a run-down building on Detroits Cass Corridor in March, 1969, as a tabloidwhich was typical of local underground newspapers at the time. Reay named the publication after his favorite band, Cream, but changed the spelling of the virtuoso supergroup and served as the de-facto editor. (For years, no one on staff had an official job title.) He left months later, though the original incarnation of Creem continued as a national monthly until 1989. The documentarys director, Scott Crawford, who for eight years edited a magazine of his own called Harp, also takes a cue from Cream. The band was made up of three members, and Crawford frames the magazines history around another trio: Kramer, the publisher; Dave Marsh, the magazines second editor; and Lester Bangs, who became its most celebrated writer after he moved to Detroit, in 1971. But Creem was always the product of a larger, continually changing ensemble. The film, by limiting its focus to three people, slights the magazines enduring legacies: an egalitarian approach that flowered circa mid-seventies punk rockas the Creem contributor Patti Smith put it, This is the era where everybody createsand a steadfast rejection of stardom that refused to accept famous musicians as different or more special than their fans.

Our bands are peoples bands; similarly, we think of ourselves as a peoples magazine, the staff of Creem declared in a 1970 mission statement. We are a rock n roll magazine, with all that that implies. Our culture is a rock n roll culture. We are rock n roll people. In practice, although the magazine held making music and writing about music to be vitally and even morally important, as the critic Greil Marcus says in the film, it never took either music or writing too seriously, approaching everything with an irreverent sense of humor. Creem is a raspberry in the face of the culture, Bangs said, in 1973, and, in a sense, its a raspberry in the face of itself.

At a time when the pop charts were dominated by cloying songs such as A Horse with No Name and Joy to the World and the playlists of burgeoning FM radio stations were heavy on James Taylor; Crosby, Stills & Nash; and the Eagles; Creem respectfully ceded coverage of those artists to Rolling Stone. It championed, instead, proto-punk bands such as the Stooges, the MC5, ? and the Mysterians, and Count Five; mavericks such as Lou Reed, Dr. John, Marc Bolan, and George Clinton; and nascent heavy-metal acts, including Black Sabbath, Deep Purple, and Alice Cooper. Unlike Rolling Stone, which is a bastion of San Francisco counter-culture rock-as-art orthodoxy, Creem is committed to a Pop aesthetic, Ellen Willis wrote in The New Yorker. It speaks to fans who consciously value rock as an expression of urban teen-age culture.

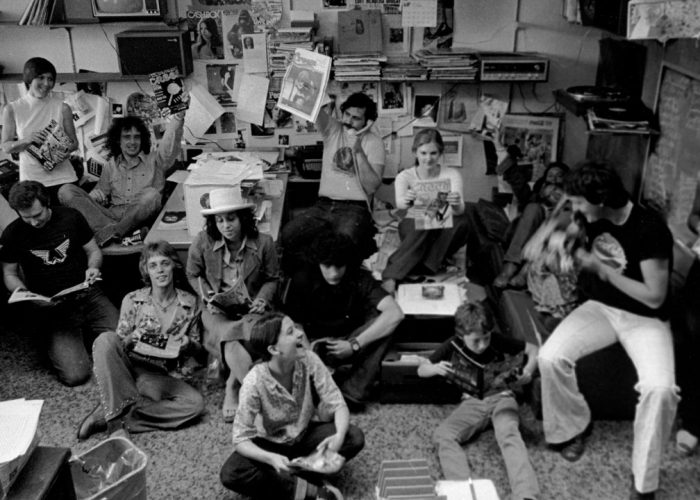

The original staffersincluding Marsh, Bangs, Jaan Uhelszki, and Roberta Crugersaw the magazine as a cross between Mad, the satirical comic book, and Esquire circa the height of New Journalism, which brought literary techniques to reporting and criticism. We were always riffing off each other, like we were doing a comedy routine, says Uhelszki, who took a cue from George Plimptons participatory journalism when she wrote the 1975 piece I Dreamed I Was Onstage with KISS in My Maidenform Bra and who co-produced the documentary with J. J. Kramer, Barrys son. It was group-think, like a hive mind, so collaborative all the time, she says. Thats a big point. That and the attitude of, as we said in the ad we used to run soliciting contributors, We aint got nothing you aint got, so what do ya got? Meaning, if we can do it, you can do it.

Indeed, many of the magazines regular contributors started as readers who wrote in to the letters column; Marsh, Bangs, and other editors nurtured these voices. But the film spends more time highlighting the snarky humor of the magazines captions, headlines, and photos than focussing on the ambition and ideas of writers such as Nick Tosches, Richard Meltzer, Richard Riegel, Richard C. Walls, Robert Duncan, Bill Holdship, J. Kordosh, and Rick Johnson.

As for the trio at the center of the documentary, Marsh left the magazine in 1973 and became better known for his work at Rolling Stone. Bangs left Creem in 1976 and moved to New York, where he died six years later, at age thirty-three, reportedly with traces of Valium and the painkiller Darvon in his bloodstream. Kramer died in his late thirties, in January, 1981, in what was ruled an accidental death. Amplifying Kramers contributions seems to be a goal shared by Crawford and J.J., but, although the film praises him for giving his writers the freedom to make a mess on the page, it misses the opportunity to follow his transformation from an idealistic sixties hippie to an eighties capitalist. In 1973, Kramer moved Creems staff from their second home, a Michigan farm commune, into an ornate building that housed a dentists office and a hair salon in a gentrified suburb of Detroit.

Try as he might, Kramer never succeeded in turning Creem into the sort of cash-cow life-style magazine that Rolling Stone became. Its steadiest advertisers included A-200 Pyrinate Liquid (one shampoo kills lice and nits), Boones Farm wine, and mail-order head shops that hawked pipes, personalized roach clips, and something called the grass mask. (Shit, what a hit!) He once dreamed of starting a British edition, a syndicated radio show, and a record labelnone of which materialized.read more

Will Creem Magazine Ever Get the Respect It Deserves?