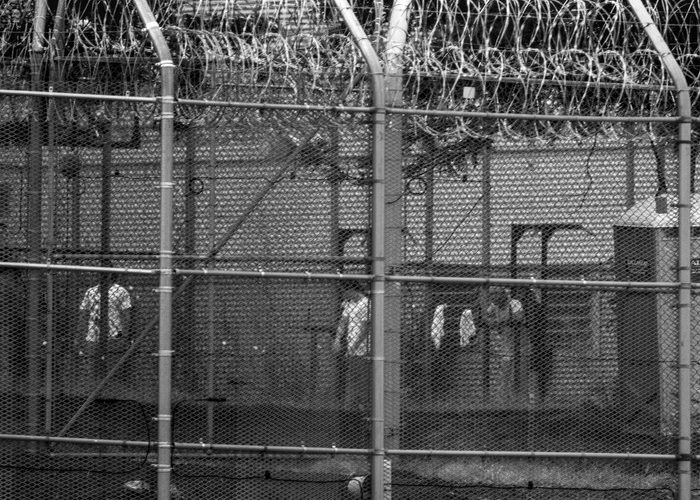

The oldest Millennials turn 40 this year, and their prospects are not looking much brighter than when they were recession-battered 20-somethings. Millennials, born from 1980 to 1996, are the best-educated generation in American history, and the most indebted for it. They are the largest adult generation, at 22 percent of the U.S. population, and yet hold only 3 percent of the country’s wealth (when Boomers were young adults, they held 21 percent). From 2009 to 2016, Millennial homeownership rates actually fell by 18 percent. A 2015 Census report found that 20 percent of Millennials live in poverty.The list of answers to “How did Millennials get here?” is long, but one reason stands out: Millennials are the incarceration generation. From cradle through childhood to parenthood and near middle age, Millennial lives have been shaped and stymied by policing and prisons.In the single decade from 1980 to 1990, thanks in no small part to the War on Drugs, the number of people in U.S. prisons more than doubled. It peaked in 2009, having exploded by 700 percent since 1972. Although incarceration rates are now declining, they are not going down nearly as quickly as they went up. Indeed, if the pace of decline continues, it will take close to a century for the number of people in prison to reach what it was in 1980. Even a more modest goal, such as halving the number of current prisoners, wouldn’t be achieved until nearly all Millennials are in their graves.[Read: Quarantine could change how Americans think of incarceration]No living generation has made it through the incarceration explosion unscathed. In 2009, nearly one in five prisoners was a Baby Boomer. Millennial timing, however, was spectacularly bad. Born as imprisonment rates were on their meteoric rise, they grew up in a country that was locking up their parents, then were locked up themselves as the number of children behind bars hit a record high, and entered adulthood in an age of still-high incarceration rates and punishments that last long after a person steps out of the cage.According to research from the Center for American Progress, one in four Black Millennials, and close to one in three younger Black Millennials, had an immediate family member imprisoned when they were growing up. White Millennial children fared better, but the statistics are still appalling: Nearly one in seven white children born in the 1980s and 1990s grew up with a loved one behind bars. By contrast, in the 1970s, when Gen Xers were kids, about one in five Black children and about one in 13 white children had a family member imprisoned at some point. In the 1950s, when Boomers were kids, the numbers were one in 10 Black children, and just 4 percent of white children.By the late 1990s, more than half of adult inmates were parents; all of their minor children, save for those still in diapers, were Millennials. Two percent of America’s children, and 7 percent of Black children nationwide, had an incarcerated parent in 1999 alone. Some 60 percent of parents imprisoned in a state facility were detained more than 100 miles from home, and more than half of those mothers and fathers said they hadn’t had a single visit from their child since being locked up.[Read: How mass incarceration pushes Black children further behind in school]Millennials were left with the scars that come when you’re small and a loved one is ripped from your household. Kids with an incarcerated parent—and the overwhelming majority of incarcerated parents are dads—suffer from higher rates of depression and aggression, and are more likely to act out than kids whose parents are free. They are more likely to grow up poor, more likely to go to jail, and more likely to experience other adverse childhood events, including exposure to substance abuse, family violence, a parent’s death, mental illness, and suicide.One study published in the journal Demography looked at the impact of incarceration on the household assets that are key to social mobility: owning a car, a bank account, and a home. Families with incarcerated fathers were much less likely than demographically similar ones to have these basic resources.Incarceration, more broadly, affects worldview. Young people who grow up in over-policed communities of color have “a very different perspective on authority, on the system, on who it’s there to protect,” Emily Galvin-Almanza, the CEO and founder of Partners for Justice—a prison-reform organization—told me when I interviewed her for my book on Millennials. “You have a whole generation of people who have grown up with no belief in the whole ‘Serve and protect’ claim, but who do know that the cages are there waiting as a trap.”[Barbara Bradley Hagerty: Innocent prisoners are going to die of the coronavirus]A lot of Millennials got trapped in those cages. They weren’t just raised by imprisoned parents; they were arrested and imprisoned beginning when they were just children. The National Longitudinal Survey of Youth found that, among those born from 1980 to 1984, nearly one in five reported being arrested at least once before they turned 18, and 30 percent said they had been arrested at least once by age 23. For Black men in this group, the numbers are even worse: 30 percent reported having been arrested at least once as children, and nearly half by age 23. Older generations weren’t spared, but their experiences with police as young adults were less extreme. A 2019 study from Johns Hopkins University found that about 25 percent of Gen Xers, and only 10 percent of Boomers, said they had been arrested in their youth.For all of the stereotypes of Millennials as perpetual adolescents Peter Panning their way through adulthood, Black and brown Millennials in particular had the exact opposite experience. They were robbed of their childhood by police and even educators, treated as delinquents and criminals-to-be rather than as vulnerable innocents.When juvenile incarceration rates peaked in 1999, every one of the 77,835 young people sentenced to confinement in a juvenile facility was a Millennial; so were the thousands of other children under the age of 18 who were imprisoned with adults. Here, too, Millennials were a particularly unlucky cohort. In 1986, when imprisoned youths were all Gen Xers, 24,883 were committed to juvenile facilities. In 2017, fewer than 27,000 kids, all Gen Zers, were committed and sentenced to juvenile facilities, according to the Sentencing Project.[Ta-Nehisi Coates: The Black family in the age of mass incarceration]Millennial contact with the prison system continued into adulthood. In 2018, the last year data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics are available, Millennials made up about half of America’s more than 1.4 million people sentenced to federal and state prisons. Although more Gen Xers than Millennials were incarcerated in 2009, America’s peak imprisonment year, the total picture is still arguably worse for Millennials because of their childhood experiences. Their futures, moreover, remain bleak. The average person in prison is 36 years old. It’s Millennials, and the Zoomers of Generation Z, who will fill prison cells for decades to come.Once people are released from prison, a new set of barriers go up. According to research from the Brookings Institution, barely half of people who get out of jail or prison find employment within a year of their release. Those who have jobs still mostly live in poverty: Their average annual income is $10,090, less than what a full-time worker would earn even if they were paid the minimum wage. A report from the Prison Policy Initiative found that the formerly incarcerated were close to 10 times more likely to be homeless than the general population.The downstream effects of incarceration also limit the extent to which the formerly incarcerated can advocate for themselves. Eleven states bar people with certain felony convictions from voting, removing the traditional avenue through which a person would participate politically and demand the kind of change necessary to address their plight. As much as Millennials are criticized for being politically disengaged, people in positions of power have intentionally muted their voices.[Read: Is this the beginning of the end of American racism?]Incarceration is far from the only obstacle Millennials have confronted, and it’s not the one and only driver of Millennial despair. Millennials have also faced spiraling costs in education, health care, housing, and child care, even as real wages have stagnated, good job opportunities have constricted, and the social safety net has frayed. But undoubtedly, policing and imprisonment made an already-precarious generation less healthy, less able to remain gainfully employed, less stable, and more vulnerable in economic downturns.As Gen Z comes of age, incarceration rates are dropping, having declined 7 percent from 2009 to 2017. But the United States still locks up a higher proportion of its people than any other nation in the world. And we still rely on punitive measures that shadow people long after they’ve served their time, making incarceration not just a temporary loss of liberty, but a lifelong albatross. One way to help the most vulnerable Gen Zers do better than their Millennial predecessors? Look to the millions of young people protesting in the streets, and the millions more showing their support by critiquing America’s racist and deadly systems of policing and incarceration. Listen to what the kids are saying, and reform the system to put justice ahead of criminalization.read more

Millennial Futures Are Bleak. Incarceration Is to Blame.