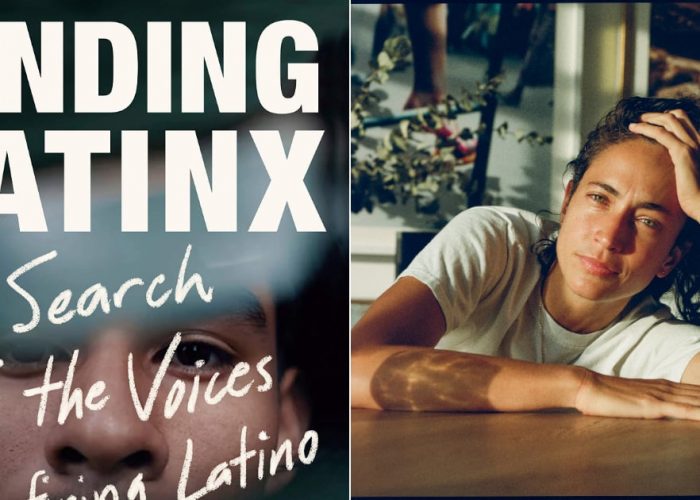

Excerpted from Finding Latinx: In Search of the Voices Redefining Latino Identity, on sale Oct. 20. Preorder the book here.

Tucked away in another corner of Miami is Allapattah, traditionally a working-class immigrant neighborhood with a vibrant Dominican community. Some even consider this part of town the last blocks to be untouched by Miami’s gentrification. As I drive through the area, I see no tall skyscrapers, no hip bars or cool coffee shops. I park the car at Tipico Dominicano, an old restaurant started in the 1980s that has long served as a refuge for newly arrived Dominicans.

I walk out to the restaurant’s patio and into a large crowd that’s gathering to discuss race and culture among the Latino community. The first thing I hear is a group of organizers asking the assembled crowd, “When you see a Latina, who do you think about?”

Everyone on that patio stares at one another in silence.

In my case, my mind immediately took me to the TV screen I grew up around: Univision. I remembered the tall, skinny women with huge busts from La Usurpadora and La Duena, my two favorite telenovelas from the 1990s. I also remembered the anchors and reporters who appeared in my dad’s newscast most of them wearing tight dresses, some of them dolled up with pounds of mascara, and all of them with their hair completely alisados, straightened. I then thought about Eva Longoria. And then about Sofia Vergara. And, finally, my mind couldn’t stop picturing J.Lo, wearing those baggy white pants and tank top, dancing in her “Jenny from the Block” music video.

Then someone followed up with, “And what about immigrants? Who do you see when you think of immigrants?”

My mind took me to the border.

I thought about the Central American and Mexican migrants I had met in McAllen, Texas, a couple of months prior. I could perfectly remember their faces as they stepped out of the shower at the respite center their first hot shower since they had crossed the border. I thought about the countless Latinos I had met throughout my work the farmworkers, domestic workers, students, and artists all of them people with titles, but all of them immigrants first. And I thought about my own family. My mind took me to Cuba and Mexico.

An older woman from the back of the patio, with weary skin and eyes, raised her hand. She said, “We are very hardworking. I started here cleaning houses, and now I’m a cashier Monday through Friday. I work very hard in this country for a better life,” she said. “For a better United States.” She was saying this as if she had to prove a point to us, almost as if she were begging for approval.

In Latino communities, brains are so conditioned to linking the words “Latino” and “Latina” to light-skinned people that the notion of anyone darker is obscured by stereotypes and social constructs that we can’t even see ourselves.

Everyone on that patio paused when this woman spoke, and I fear it’s because many of us had the same realization in that moment. Nowhere in our minds did this woman surface: the image of an Afro-Latina. In Latino communities, brains are so conditioned to linking the words “Latino” and “Latina” to light-skinned people that the notion of anyone darker is obscured by stereotypes and social constructs that we can’t even see ourselves. In Latin America, governments and Western civilization erased all trace of Latinos who are of African descent; as a result, those who share bloodlines with enslaved Africans, who survived at the mercy of colonialism and lived in the shadows of history, haven’t always had a place in their own countries.

During the colonial period of 1502 to 1866, more than eleven million enslaved Africans were forcibly shipped to the New World, and a number of them ended up in the Caribbean, South America, and Latin America. As has been reported by the historian Henry Louis Gates, Jr., many Latin American countries enacted policies to “whiten” their states after they received enslaved Africans into their land. To increase their white population, governments encouraged migration into their countries of white families and also encouraged interracial mixing as a means to whitewash the darkness. Yet even centuries after this period, Afro descendants in Latin America were barely recognized as human. It wasn’t until the 1980s and 1990s in large part because of local social black movements in countries like Brazil, Colombia, Panama, and Honduras that governments across Latin America started adding racial data to their national censuses. That fight is far from over now. The Mexican government has yet to unanimously recognize Afro-Mexicans in its national constitution. The more than one million Afro-Mexicans who live in the country aren’t even guaranteed constitutional rights as of now (pending final congressional approval). In fact, it wasn’t until 2015, when the government included Afro-Mexicans in the official national census after being pressured by activists, that the country even bothered to recognize the existence of this community.

But, no matter how hard you try, you cannot truly erase facts and history. According to the Pew Research Center, “In Latin America’s colonial period, about 15 times as many African slaves were taken to Spanish and Portuguese colonies than to the U.S.” That’s why today, centuries later, there are approximately 130 million people with African roots living in Latin America. Per Princeton University’s Project on Ethnicity and Race in Latin America, that’s about one-quarter of the continent’s population.

The challenge for many Afro-Latinos is that the public simply doesn’t know how to categorize them. On the one hand, Americans don’t see them as African Americans. On the other hand, Latin Americans don’t see them as Latinos. People are accustomed to seeing blackness through one lens.

The challenge for many Afro-Latinos is that the public simply doesn’t know how to categorize them. On the one hand, Americans don’t see them as African Americans. On the other hand, Latin Americans don’t see them as Latinos.

Back in Allapattah, one of the event’s main organizers, a young woman in her twenties, raised her hand at the front of the patio. She wanted us to give her all our attention, and looking straight into the crowd, she said forcefully, “Fifty thousand Haitian immigrants are at risk of immediate deportation after Trump ended Temporary Protection Status for Haitian refugees. These are the images we have to keep in mind, and the people we have to keep in mind, because our media is not accurately articulating who are some of the most affected populations in the immigration debate.”

She was absolutely right.

When the organizers at Tipico Dominicano initially tossed the word “immigrants” at us, my vision was so hyperfocused on the U.S.-Mexican border that I left everyone else behind the black undocumented immigrants coming from the Caribbean, the Afro-Latinos who were neglected in the migrant caravan, or all the immigrants who crossed borders not by feet but by plane or by sea, in the air, and over waves.

Immigration, too, it dawned on me, was a story centered around a very specific backdrop in the United States, a very specific landscape, and a very specific series of protagonists: starring the border and featuring brown people. But what about those who never made it on the screen? What about the lost voices overshadowed by their own darkness? The ones that were dismissed as “too black’ to be Latino or “too dark” to even get in the back of “the immigration line”?

The very intent of the event I was at was exactly that: to push the audience to ask these questions, to challenge our own biases, and to expand our understanding of our very own people. That afternoon, we found ourselves in the backyard patio of Tipico Cafe, a Dominican restaurant in Allapattah. Then, as people were waiting to watch Omilani Alarcon’s documentary, LATINEGRAS, I sat quietly in the audience and observed my surroundings. To my right, a young Afro-Dominican was telling her friend how she was taught as a young girl to always walk in the shade in order to avoid getting any darker. To my left, I overheard a black Nicaraguan indigenous woman say: “People think we are weird.” And right behind me, a young black Puerto Rican girl recounted how, as a kid, her parents would always straighten her hair so she wouldn’t have “pelo negro.”

From FINDING LATINX: In Search of the Voices Redefining Latino Identity by Paola RamosCopyright © 2020 by Paola RamosPublished by arrangement with Vintage Books, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC

Image Source: Courtesy of Penguin Random House LLCread more

Paola Ramos on Afro-Latinx: “No Matter How Hard You Try, You Cannot Truly Erase Facts and History”

of course like your web site however you need to test the spelling on several of your posts.

Several of them are rife with spelling problems

and I in finding it very troublesome to tell the reality nevertheless

I will certainly come again again.

Yes I working on that. Come back, it is much improved in the future. I working to capture as much real news as I can and keep current. Thanks for the comments.

Homer

Hey! Someone in my Myspace group shared this site with us so I came to check it out. I’m definitely loving the information. I’m bookmarking and will be tweeting this to my followers! Outstanding blog and fantastic design and style.|

Greetings! Very helpful advice in this particular article! It is the little changes which will make the greatest changes. Thanks a lot for sharing!|

Hi I am so happy I found your webpage, I really found you by error, while I was browsing on Bing for something else, Anyhow I am here now and would just like to say thanks a lot for a incredible post and a all round interesting blog (I also love the theme/design), I don’t have time to read through it all at the minute but I have book-marked it and also added your RSS feeds, so when I have time I will be back to read a lot more, Please do keep up the superb work.|

Appreciate the recommendation. Will try it out.|

Very nice post. I certainly love this site. Keep writing!|