In his lifetime, Martin Luther King Jr. was both revered and loathed, beloved and hated. An outspoken voice on behalf of equality and justice for Black Americans, he was feared by the white establishment, seen as a threat to the social order. And that reputation is especially evident in who chose to closely monitor his activities, tap his phones, and attempt to blackmail him into suicide: the FBI.

The FBIs scrutiny of King is the subject of MLK/FBI, a new documentary from Emmy-winning director Sam Pollard. Leaning on newly declassified documents about the Bureaus surveillance of King under the leadership of J. Edgar Hoover, the film explores in detail how the FBI tracked King and what kind of threats it claimed he posed to America. MLK/FBI shows how decades of Hollywood portrayals of Black men and the FBI contributed to perceptions of King. And it doesnt shy away from how the FBIs invasion of Kings privacy turned up facts about his life and marriage that complicate his legacy.

In many ways, its the perfect film to watch early in 2021 an examination of government overreach, entertainments effects on American imaginations, and how little has changed in the way that establishment voices so often try to silence Black activists. I spoke with Pollard about making the film, Hollywoods exaltation of FBI agents and cowboy figures, and the responsibility filmmakers have to help audiences see three-dimensional characters.

Whenever theres a big moment in the news like protests against police brutality last summer or riots at the Capitol last week, for instance people start quoting Martin Luther King Jr. But often it seems like people are just appropriating his words for their own cause, rather than putting his quotes in the context of what he actually worked for. How do you approach an icon like King when youre making a film about him, knowing how often he is misrepresented?

I would first say that I try not to see anybody, no matter how special, as iconic. I try to see them as human beings, knowing that they did great things. Thats how I define Dr. King. Hes a human being who did great things. Nobody, nobody walks on water, not even Dr. King.

As a documentary filmmaker, the films I tackle, the subjects I tackle, the folks that I tackle, Im trying to show them in all of their complexity, as much as I can knowing full well there may be things that will come down the pike years later that will unearth even more about them. That was the agenda and the goal of doing this film, about King and J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI. To dig into who they were, what they were all about, and understanding that a lot of what weve seen in this country in the past week is systemic in terms of the DNA of this country.

A scene from the March on Washington in MLK/FBI.

IFC Films

What we saw last Wednesday, it wasnt an anomaly. No one should think, Oh, my god, how could this happen in America? It happened every day, many, many years ago, all around the country. When Black communities were self-sustaining, and white people outside their community saw it and didnt like it, they said, We dont want those communities to exist. They would go in there and they would kill people, they would maraud and they would destroy those communities. The Tulsa race massacre in 1921. The Red Summer of 1919. This is not an anomaly. Black people were being lynched and murdered like this, because other people said, We dont want you to have a voice. We dont want you to go near our white women. This is America, man.

I was reading news coverage and discovered that one of the rioters, a well-known proponent of QAnon, the one wearing the horns, claimed he was engaging in civil disobedience like Dr. King. I saw other people quoting Dr. Kings line about how a riot is the language of the unheard. It seems like ironically, given history people twist Dr. Kings words for their own ends.

Listen, heres the big difference. When King and his folks demonstrated in America, they did it peacefully. They did not attack some building or some people and say, We want our voices heard. They did it peacefully. They banded together, they marched together, they did sit-ins. Imagine these young Black college students in the late 50s, early 60s, doing the sit-ins, where they would have milk thrown on them. Theyd be dragged out of chairs. They would be arrested and locked away because they were doing peaceful demonstrations.

Thats a complete difference from what these people were doing last week. They should be ashamed that they even put Kings names in their mouth. It was civil disobedience with Dr. King and the SCLC movement. [Note: The Southern Christian Leadership Conference is the Black civil rights advocacy organization founded by King that spearheaded events such as the March on Washington and the Selma voting rights movement.] That was civil disobedience. This was not civil. This was armed insurrection. Big difference.

You said you dont like to think of anyone as an icon you prefer to see them as a complex human being. That seems tricky when youre making a documentary because people sometimes dont like to see leaders as complex. When they put someone on a pedestal, and then that person is shown to be a full, three-dimensional human being, it frustrates them. So as a documentarian, how do you approach your work?

Heres the responsibility I have as a filmmaker, which has evolved over the years. Its to look at these characters, these human beings, these real-life people, as real people. To look at someone like Dr. King as a human being who had, like many of us, a very complicated life. For example, here was a man who became not that he wanted to become, but when he became the leader of the movement after the Montgomery bus boycott. He goes on to form the SCLC, knowing full well that its going to be an uphill battle. But he believes in it. He believes in the notion of integration. Theres a man who understands that hes going to catch brickbats from white people. And sometimes Black people say, Why do you want to do all of that? Why cant we just leave everything alone? You know, why cant we all just get along?

Heres a man who leads a group of people to the March in Washington, who basically said, We want better jobs. We are going to be integrated. Heres a man who understood that he was going to be watched and monitored by the FBI. Here is a man who had a very complicated personal life. Here was a man who, by 1967, realized he couldnt just be a voice about the civil rights movement. He wanted to be a voice about the fact that America should not be in Vietnam, knowing full well that he would catch pushback from not only those in the civil rights community, but from LBJ and the Johnson administration, who was a close ally up to that point.

This was a complicated human being who understood all of these things he had to deal with on a daily basis. It wasnt an easy journey, but was the journey he knew he had to take.

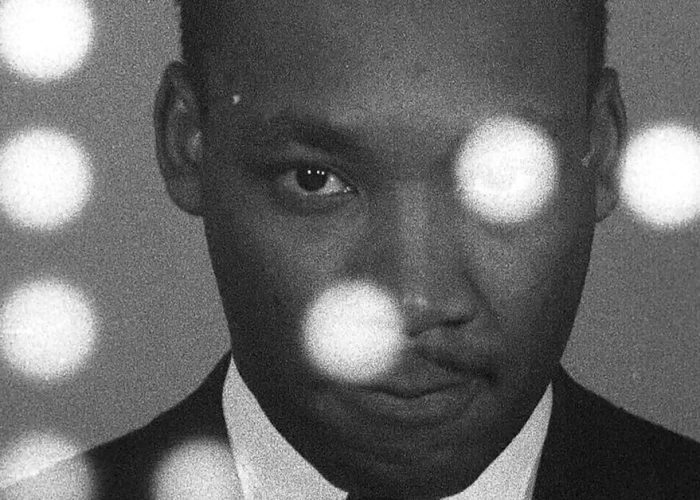

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in Sam Pollards MLK/FBI.

IFC Films

In this film, youre bringing parts of Kings life to the screen that arent unknown, but might be unfamiliar to some of the audience. For instance, the depth of the FBIs surveillance of him may surprise the audience, and it has some really serious implications. How do you present that in a way that will really hit home with the audience? Whats your process?

The process is this: You do your research as thoroughly as possible. You try to find the voices that can help articulate the story, particularly in a documentary. And you try not to create tabloid filmmaking. You try not to make it so its like, Oh, my god, look what King did. Wasnt it terrible? Thats not the job. My job is to show you King and all of his colors. To show you Hoover and all of his colors. To break down the mythology of the FBI. Thats my job. Thats what I feel that my job is.

Ben Hedin, my producer, and I asked the same question when we were doing the film: Are we doing exactly what the FBI had wanted to do when they were initially monitoring King? And we had to come to grips with that. In some ways, we are coming close to that, but we werent going to do it the way the FBI was gonna do it. We were going to do it in a more responsible way. To leave something open-ended so you as the viewer can say, Well, I see what Sam has done, and Im not sure how I feel about it. Maybe I need to hear the tapes, when theyre released in 2027. Thats what I want an audience to come away with. I dont want you to be able to say, Oh my god, look what Sam did, its horrible about Martin Luther King. Thats not the point. The point is to show you that theres layers of gray in every human beings life.

One thing you do really well in the film, something thats really powerful to see specifically onscreen, is show how cinema has been complicit in creating ideas about what the FBI is like, and also what Black people, and Black men in particular, are like. Theres a long history in Hollywood to delve into there.

At the beginning of the edit, I told [editor] Laura Tomaselli that I thought there was some archival material we ought to dig into, some old movie clips. I was very familiar with a lot of these old movies about the FBI because Im an absolute movie nut. Ive watched all kinds of movies. So I went home that night and I put together a list of movies that I thought she should get DVDs of so we could find certain things that we thought would be appropriate. I had Walk a Crooked Mile (1984), with Dennis OKeefe and Louis Hayward. I Was a Communist for the FBI (1951) with Frank Lovejoy. Big Jim McLain (1952) with John Wayne. The FBI Story (1959) with Jimmy Stewart. And the seminal TV series I grew up with in the 60s, The FBI. I was very well aware of those shows. And I said, We can use those shows to dig into the mythology of the FBI.

The other thing thats always important when youre doing these kinds of archival documentaries is that you want to have a really good archival producer who can dig into that material to find stuff that you hadnt seen before. So for example, the material that [archival producer Brian Becker] found of Dr. King, with his wife and his kids when they were young, and his parents Id never seen that before. When he was able to locate the footage with the FBI, with Scotland Yard having in custody James Earl Ray [who was later convicted of Kings 1968 assassination], I had never seen that footage before. This was eye-opening for me. Thats what always fascinating about documentaries. In some ways, we almost see ourselves as archaeologists, going on a dig, unearthing some new specimen that has some historical resonance. Its like, wow. After all these years of making films, as an editor, as a director, as a producer, I still can carry the wow factor. I havent grown that cynical. [Chuckles]

Watching all these FBI clips in the film, I found myself wondering: Why have we historically been so obsessed with seeing the FBI onscreen as heroes and good guys?

Its called creating propaganda, very successful propaganda. Heres a man [J. Edgar Hoover] who was the FBI director for over 40 years. He was a man who basically said, I need to paint a portrait of this FBI that the American public will buy into. So you see even in the archival footage or stills, images of J. Edgar Hoover with the Tommy gun, you know thats not real. Thats all made up because he was trying to make sure that it comes across as the FBI are heroes. Hes with those little boys who say, I really want to be an FBI agent, like you, Mr. Hoover. Thats part of developing propaganda.

Listen, Alissa. Youre looking at me, a Black man who grew up in the 50s and 60s. You know what I wanted to be when I grew up? A cowboy. Why? Because American propaganda has established in the movies and in the books and on television shows that the American cowboy made the West oh, we killed some Native people, but thats not the point. We made the West.

Its about developing propaganda about who you are, and who you want to be. Look at Donald Trump. The reason that the damn man is so successful is that hes a phenomenal propagandist. He knows how to spin the tale. Thats why hes got these people in such an uproar. He can spin the tale. Hes a salesman.

And America is about that. Every country has to build themselves up on propaganda. When I grew up, I would watch these movies about the great British Empire. All I could think of was Cary Grant and Gary Cooper and David Niven. And oh, there were some Indian people that they would be suppressing. Oh, really? Propaganda. And it continues to this day. We see it every day.

You could say Hollywood has created an alternate history for us that most people believe. Because images are so powerful.

Because Americans arent thinking people. We dont reflect, we just react. We dont reflect. It took me a long time to realize, oh, John Wayne was a right-wing, insane human being sometimes. I gotta be mindful of what I was seeing in those films. When you watch a film like The Searchers [the 1956 Western in which Wayne plays a Civil War veteran], to me, John Ford really showed us a racist white man. I dont know if he understood what he was doing. But thats what he showed us. That was the truth. America is about creating not just America, every place is about creating myths. Thats part and parcel of how you get people to follow you.

A scene at the FBI as scene in MLK/FBI.

IFC Films

Another thing you delve into really well in the film is what Hollywood has done, unfortunately, to the image of Black people and Black men in particular, and how that played into how people saw Dr. King and the people he was working with.

It was one of two myths about Black men. They were either scared of their own shadows, like Stepin Fetchit or Willie Best, or they were brutes, Black bucks, who you couldnt trust around your white women. And if they got near a white woman, you had to destroy them. You had to lynch them, you had to disembowel them. This is about presentation its all about presentation.

So we thought it was important to see that. I remember the first time I saw those images in [the 1915 film] Birth of a Nation, of Black men in Congress with their shoes off, eating watermelon and stuff. And I said, Whoa, man, whats [director D.W.] Griffith doing? He basically is demonizing Black people and Black men, saying, See, thats why they cant be in control in the government. Thats why they cant be in office, because they are lazy. They are sex addicts. America is … [sighs] Im an American. But man, does it come with a lot of baggage.

Sometimes it seems like filmmakers, in trying to combat those old stereotypes, end up feeding back into them.

Go back and just watch Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. And watch the sequence where Brad Pitt is confronting the actor who plays Bruce Lee. Youre gonna walk away with the idea that Brad Pitt, this white man, could kick Bruce Lees ass. Now, whoa. You know, and I know, that Brad Pitts character could not have kicked Bruce Lees ass. They stopped it before they really get into it, but youre not going to remember that. Youre going to remember that the first time Bruce Lee throws him against the car, but the second time, he throws Bruce Lee. Its all in how you present these things.

Youve got to be able to look at it and understand it. Listen, I walked away from the movie saying, Man, Brad Pitt is the star of that movie. But I understood underneath what was going on, what Quentin [Tarantino] was doing. I understood it. But thats not what usually happens when we watch movies. You watch a movie and you buy into the myth. If the director does it well, you buy into the myth. You want to go out and be Dirty Harry. You want to go out and be Charles Bronson.

Do you think filmmakers have a part to play in helping create better literacy about characters and about history?

[Leans into camera] Spike Lee. [Pause] That says it all, Alissa. Spike Lee. Thats been his agenda ever since Ive been making these things. Thats what hes all about.

You see what he did with Da 5 Bloods. Look at what he did. This is what you do, if youre a filmmaker who really understands the complexity of people. He has these Black men, these Vietnam veterans theyre not all monolithic. In their experiences as Black men, they all come to the table with different points of view about what it meant to be a soldier and a Black soldier in Vietnam. Thats complexity. Thats looking at people as human beings and seeing that theyre all shades. He doesnt paint them all one way. Theyre all different. Thats what your job should be as a filmmaker, in my opinion.

Why does Hollywood fail on this so often? Is it a failure of imagination?

Its not a failure of imagination. Its basically saying, We want to paint the world a certain way, and that way is the way we want this world to look. Thats all it is. The people in charge for many years wanted the world to be painted a certain way. Thats what I was raised on. I was raised to see John Wayne as tall in the saddle. I was raised to see Jimmy Stewart or Gary Cooper as the tall taciturn hero. Movies were supposed to shape certain mythologies, how you are supposed to walk away, thinking about what it meant to be an American. It wasnt a lack of imagination. It was thought out.

Controlling the narrative.

Exactly. I mean, I do the same thing. Im trying to control the narrative. Trying to make it a little more complicated.

When we talk about controlling narratives, it seems clear that there are a lot of parallels between how the FBI used the word communists back in the 1960s, and the way people use words like antifa today words that start to lose connection to their actual meaning. Do you see those parallels? And is there a way to avoid recreating the mistakes of the past?

Only if you want to. If you dont want to, you will still recreate them.

We still live in a society where many people have a one-dimensional perspective of what it means to be an American. Thats why what we saw last week reverberates what happened in the 60s with King, and Hoover, and the FBI, and America in Vietnam. Many Americans have a one-dimensional perspective. Its all about who we are. We dont care about anyone else. Unless youre going to come to some reckoning and understanding that we always lived in a diverse and complex society, but there was a lack of inclusion, youre gonna still pull out the same tropes.

History rhymes with the present.

IFC Films

Back then it was, King, oh, my God, he is flirting with communism, and theyre gonna help destroy America. Then we fast forward and someone says, Oh, Black Lives Matter is flirting with antifa and theyre going to destroy America.The same tropes are being pulled out all the time. The dog whistles that you heard in the 60s are the same dog whistles you hear today. Theres a lady on a television show in the film who asks Dr. King, Dont you think that peaceful protesters are causing the riots? Didnt we hear the same thing about the Black Lives Matter movement? Arent they causing the riots in the cities? Arent you people moving too fast? Its the same stuff. Its a part of the fabric of America.

So in your experience, making this film, did you discover anything while making it? Did anything surprise you? What did you learn?

I learned simply like I learn with every film I do now that its a really complicated world. You have to hunker down as a filmmaker and want to deal with it on all its levels of complexity. Thats what I learned. Was I surprised at what I learned in the film? No, I wasnt surprised, because to me, its America. Last week, I said, I was angry, I was upset when I saw the Capitol building, but I wasnt surprised.

Im a Black man in America. This is pretty much the norm. When youve seen Black men and women shot down in the streets, when you see a man shot in the back, and theres no charges against the police officer who shot him, that says it all to me. So I wasnt surprised by what we did in the filming. To me, my job was to open it up and explore it so people could engage in and grapple with it. Thats my job.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

MLK/FBI is opening in limited theaters and on digital on-demand platforms on January 15. See the films website for full listings.

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that empowers you through understanding. Voxs work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts to all who need them. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today, from as little as $3.read more

How the FBI’s surveillance of Martin Luther King Jr. was bolstered by Hollywood